global reggae

dr carolyn cooper

dr cooper i’d like to welcome you to powder. it is a pleasure to have such an esteemed and accomplished writer and academic as yourself here to speak with us.

you’re jamacian born. last year jamaica celebrated its fiftieth anniversary of independence from the colonial rule of britain. what changes have occurred since independence? have things improved for the majority of the population?

On February 3, 1661, Jamaica became the first British colony to receive its own arms. The Latin motto grandly declared: ‘Indus uterque serviet uni’ (Both Indies will serve one). From East to mythic West, colonial relations of domination were inscribed in heraldry.

At Independence, three centuries later, the national motto was changed to “Out of many, one people”. Though this might at first appear to be a vast improvement on the servile Indies, both East and West, the new motto does encode problematic contradictions. It marginalizes the nation’s black majority by asserting compulsively that the idealized face of the Jamaican nation is multiracial. In actuality, only 7% of the population is mixed-race; 3% is European, Chinese and East Indian combined; and 90% is of African origin.

Over the last fifty years, black people have contested the motto, Rastafari being one of the most vocal groups in the society to assert an African identity. The political elite is now predominantly black but this does not mean that the interests of the black majority are necessarily taken into account. The Jamaican economy is still controlled by minority

groups. In some ways, nothing much has changed since Independence.

All the same, Jamaica’s vibrant popular culture has functioned as a drumbeat of resistance to social and economic oppression. The philosophy and practical wisdom of Marcus Garvey have motivated Jamaicans to claim the black power of self-determination. As Jimmy Cliff sings so potently:

Well, the oppressors are tryin' to keep me down

Making me feel like a clown

And they think that they have got me on the run

I say forgive them, Lord

They know not what they've done

'Cause as sure as the sun will shine

I'm gonna get my share now, what's mine

And then the harder they come,

The harder they fall, one and all.

your ancestry stems from the maroons a group of slaves who escaped and set up free communities in the mountains of jamacia in the eighteenth century. they also staged resistance actions against the british sugar plantation owners. how has this maroon heritage shaped you throughout your life and how has it affected jamaica as a whole?

My paternal great-grandmother Sophie was an Accompong maroon. I learnt about her when I was adult. So knowledge of my maroon heritage didn’t actually shape my identity. Oddly enough, I think my upbringing as a Seventh-Day Adventist helped to define me as an ideological ‘maroon’. We grew up with this compelling conviction that we were a ‘chosen people’ on the narrow road to heaven – unlike ‘outsiders’ who were on the broad road to destruction. We went to church on Saturday and other Christians went on Sunday. We didn’t follow the crowd. Ironically, it is this very spirit of going against the grain that made me completely confident to reject Adventist doctrines I found problematic.

In general, Jamaicans are quite ambivalent about the Maroons. Their fierce resistance to slavery and their assertion of political autonomy are unequivocally celebrated. Queen Nanny, who fearlessly led her people to victory against the British, is a national heroine. But Maroons are also seen as traitors. One of the terms of the treaty they signed with the British in 1738 required them to return new runaways to plantation slavery.

reggae music and the culture that surrounds it is important to you in both your personal and academic life. why did such unique music evolve out of jamacia and what does reggae mean to jamaican culture in general?

As Bob Marley puts it, reggae is “a riddim resisting against the system”. Reggae is also lyrics that chant down systems of oppression. The dread conditions of Kingston’s concrete jungle forced a generation of sufferers to sing redemption songs. Music became therapy for the oppressed.

you’ve published two books of your own and recently you edited a series of essays under the title global reggae. how did this book come to fruition?

In 2008, the Institute of Caribbean Studies at the University of the West Indies, Mona, Jamaica convened an international conference on Global Reggae: Jamaican Popular Music A Yard and Abroad. It was an idea I’d conceived almost a decade earlier. It was not until I was appointed as Director of the Institute that I was able to consolidate support for the conference. Keynote speakers were invited to share their analysis of the ways in which Jamaican reggae has been appropriated and adapted in a variety of cultural contexts across the globe. The book brings together all the keynote lectures.

what should people who pick up a copy of global reggae expect to come away with from it? what specific subjects would you like to mention that the essays delve into?

As I say in the introductory chapter, a recurring theme of the book is the way in which reggae adapts to suit the needs of people from Kingston to Capetown, from Brazil to New Zealand, and so many other places across the world. Global Reggae documents the ‘glocalisation’ of Jamaican culture. Over time, as reggae is adopted and adapted, the Jamaican model loses its authority to varying degrees. The revolutionary ethos of reggae music is translated into local languages that express the particular politics of the new cultural context. The echoes of the Jamaican source gradually fade. I would like readers to recognise the ways in which reggae has influenced global popular music and has also been transformed in the process.

the cover of global reggae seems to take you right into a dancehall happening; while the design of the book as a whole is striking; could you tell us a little about this?

The cover was designed by the Jamaican graphic artist Michael ‘Freestylee’ Thompson, whose work I discovered on the Internet. I was immediately engaged by the brilliance of his posters and got in touch with him through the editors of Riddim magazine, Ellen Koehlings and Pete Lilly, who had done a feature on his reggae posters.

When I saw that image of the selector on the sound system, I immediately knew it would be ideal for the book cover. It vividly illustrates travelling sounds. Michael describes himself as “Freestylee: Artist Without Borders”. Like reggae music, his politically engaged posters cover a wide range of issues across the globe; visit his photostream.

Michael is the co-founder of the International Reggae Poster Contest, along with Maria Papaefstathiou, a brilliant graphic artist from Greece, who designed the Global Reggae book. Here’s the link to Maria’s popular blog, graphicartnews.

you’re an aficionado of both the reggae and dancehall scenes. for us laypeople out here, could you explain to us what the actual difference is between the two music styles?

I’m not an expert on music, so here’s a quote from Peter Ashbourne’s chapter in the Global Reggae book which answers that question:

“Dancehall has two distinct periods: the first covers the material that uses contemporary reggae patterns and recycled rhythm tracks for accompaniment, with occasional departures from that formula. The second phase is demarcated by the accompaniment, which no longer uses reggae patterns but has a unique sound. Part of the new sound involved the use of electronic music instruments. Drum machines replaced the trap set, and synthesizers could substitute for any of the other instruments. Even when technology made sampled instruments a practical reality (this means more faithful duplication of acoustic instruments), the resulting sound was coupled with vocals that employed chanting/talking in rhythm. Dancehall became a fully matured style.

“One may now even be able to identify a third period of dancehall, as, currently, the trend is towards a ‘retro’ use of the venerable one drop. Singers are making a comeback and some riddims (rhythms) (not all, by any means) are sounding more and more like normal rhythm tracks for songs. All this is happening while the tempos for the regular dancehall are going up even more, and riddims are appearing with great frequency”.

what led you down the path to becoming such an outspoken social commentator and academic? which people influenced you to take that step beyond?

I suppose it was just intellectual curiosity. When I decided to become an academic I knew I wanted to focus on Caribbean literature in my research and teaching. And then I became interested in popular culture under the influence of my teachers and later colleagues at the University of the West Indies: Edward Baugh, Maureen Warner-Lewis, Mervyn Morris and Gordon Rohlehr. I’ve designed a popular undergraduate course, “Reggae Poetry”, which analyzes reggae song lyrics as poetry. This semester we studied the lyrics of Jimmy Cliff, Burning Spear, Peter Tosh, Bob Marley, Steel Pulse, Buju Banton and Tanya Stephens. I’ve been teaching the course for seven years now and introducing the dancehall generation of students to the reggae classics. Three years ago, one of our bright literature majors, Sheldon Reid, discovered Peter Tosh in the course! I was horrified. But it wasn’t his fault. It’s the radio stations that don’t play enough reggae and it’s the school system that doesn’t teach reggae. Sheldon did such an excellent essay on Peter Tosh I arranged to have him speak at the Peter Tosh symposium held in October 2010. And his essay was published in the Jamaica Gleaner: Peter Tosh Chants Down Peace.

As a teacher, I’ve tried to be as inspirational as the best of my own teachers.

you’re also an outspoken feminist; how would you say life for women is in jamaica today. what challenges do women face in the jamacian setting?

Many Jamaican women face the severe challenges of economic disadvantage. Working-class women especially struggle very hard to bring up children, many times on their own. Middle-class women have things much easier. They have decent jobs but they often hit their head against the glass ceiling. Patriarchy still sets limits for women. I don’t know when we’ll ever get a female Vice-Chancellor for the University of the West Indies. Then there are the perennial problems of sexual abuse that women of all social classes and all age groups have to confront.

as the feminist discourse progressed, theorists moved from the term feminism to that of feminisms as it became apparent that many of the early ideologies applied mainly to middle class, european women. as a feminist of african descent what do you see as the major challenges women from southern developing countries face that differ from those of women of the developed north?

Women from the north tend to have an economic advantage over women from the south. But money isn’t everything. Women from the south know that children are wealth – even when it’s a struggle to bring them up. And we know how to improvise – as we say in Jamaican, ‘turn wi hand mek fashion’. It’s that creativity which keeps us going. Female reggae artists sing about the battles women have to fight and this sense of solidarity is empowering.

and what is next for you dr cooper? do you have any new projects on the horizon?

I have a long-outstanding project which I hope to finish this year: an edited collection of essays on the work of Erna Brodber, a Jamaican historical sociologist and novelist. I’m also editing a collection of my own essays on Caribbean literature. My academic reputation is based on the work I’ve done on popular culture. I want to go back to my roots in literary studies.

thank you dr carolyn cooper for your discussion with us here at powder. here’s to the success of global reggae and a shout out of respect to you.

Many thanks to you for introducing me to a new audience!

check out dr carolyn cooper’s blog jamacia woman tongue

buy global reggae at uwi press

or buy it at amazon

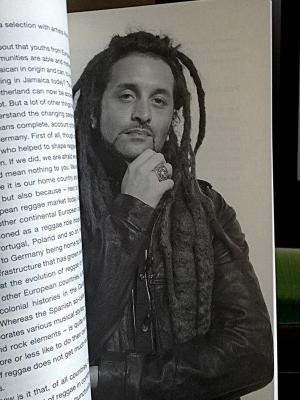

image of dr cooper by vidal smith jr photography

cover design of global reggae by freestylee, artist without borders

book design of global reggae by maria papaefstathiou

international reggae poster competition and dub posters by freestylee, artist without borders